Somewhere in 2008 or maybe Somewhere else

Moma used to tell me stories about KooKoo and who he used to be, how he could lift two goats, one in each arm, and jump over hoops at the same time. She told me about the time I nearly drowned, how ‘a huge wave swept me away,’ my body sinking off the shore of Germany. It was Kookoo who came that day to stop my tumble and save my body from the hard dried salt.

KooKoo was a man of the people. He saved my sister from a zebra, and my brother’s flip flops from a monkey, Kookoo, carried boxes up a mountain for my mother and gave me Barbari when it was still warm. Kookoo used to say, ‘you all think I’m crazy, but when I’m gone, I’ll be the only normal you used to know.’

Kookoo was born in April, an Aries with a Leo soul. The animal he was thought to have wrestled, like a Hercules with a mullet, like a godchild with hands made of gold. Some days Kookoo didn’t have arms, though, instead he worked only through words, telling stories about his childhood, and my own. ‘You were born in April’ he would say ‘An Aries, with a cancer soul.’ Like the supporter of the hydra, like a resident of a steaming marsh.

No one knows what happened to Kookoo. If he ran away to Kerman, if he fell off a cliff into the sea, or if he is still living on our street, waiting to jump out one day and say, ha! I got you real good. Everyone always called him Kookoo because his real name was boring; it meant ‘Like the sun.’ Kookoo wasn’t like the sun, though. He wasn’t too much. He was more like a fever burning up before he was gone for good. When I asked my mum about what happened to Kookoo, she said, ‘I no longer know.’ When I asked Moma, she mumbled like a broken heater before saying, ‘Kookoo was my brother, I was 26 when he was born.’

Two months after his disappearance, my family fell apart, it crumbled like Sholeh Zard and spun around until it knotted into a crown. My mum would say ‘we survived a war, we can survive this.’ but her voice began to waver now, and all her cooking curdled into soured milk. In the evenings she hid behind the purple sofa in the room with tiles the same colour as the kitchen sink. She would say ‘this room is it’s own entity, this house is one with no soul.’ That room became a garden overflowing until It got too hard to breathe, the walls a different shade now and the floor cracked in two. I asked her what could be done to save it but she was too far gone to speak.

That spring became one of silence, one where nothing moved until you asked it not to. That was when our mornings turned into evenings, and when the rocks in our stomach got too big and made us want to puke. That was when I started to call myself the corn puff king because I wanted to and because if Kookoo had another name, why couldn’t I. That was when our house grew smaller with sadness until it collapsed in on itself like the rotting tree. In the evenings we sat in separate rooms from each other, locked away behind walls of satin. When the sun set nobody moved, staying still with the heat crept.

When I think about that time, I could tell you everything and nothing. I could point out all the details but leave giant holes in the parts that you miss. I could say ‘back then I thought I looked like an English Adder,’ But not be able to tell you the colour of the sky when my mum cried over knotted silk. I could tell you how my ears were always ringing but leave out the part where I began to look like a child.

When anyone talked about KooKoo back then, I could feel the holes in my lungs being battered by heavy waves. Some days we wouldn’t talk about him though, and when we did, his name was all wrong. Moma would say ‘I miss my brother Kourosh.’ and I would ask ‘Who is he ?’ Kourosh was a fake name, one that rolled off the tongue in an unfamiliar way, one that tasted like dried cinnamon and made you want to cough. Kourosh was a Sun, but Kookoo was something else, something that was different in a way we all knew so well. I used to wonder if my family had sent him away, if they knew exactly where he was, but then I remember that Kookoo left in the evening, before anyone could see him walk out the door.

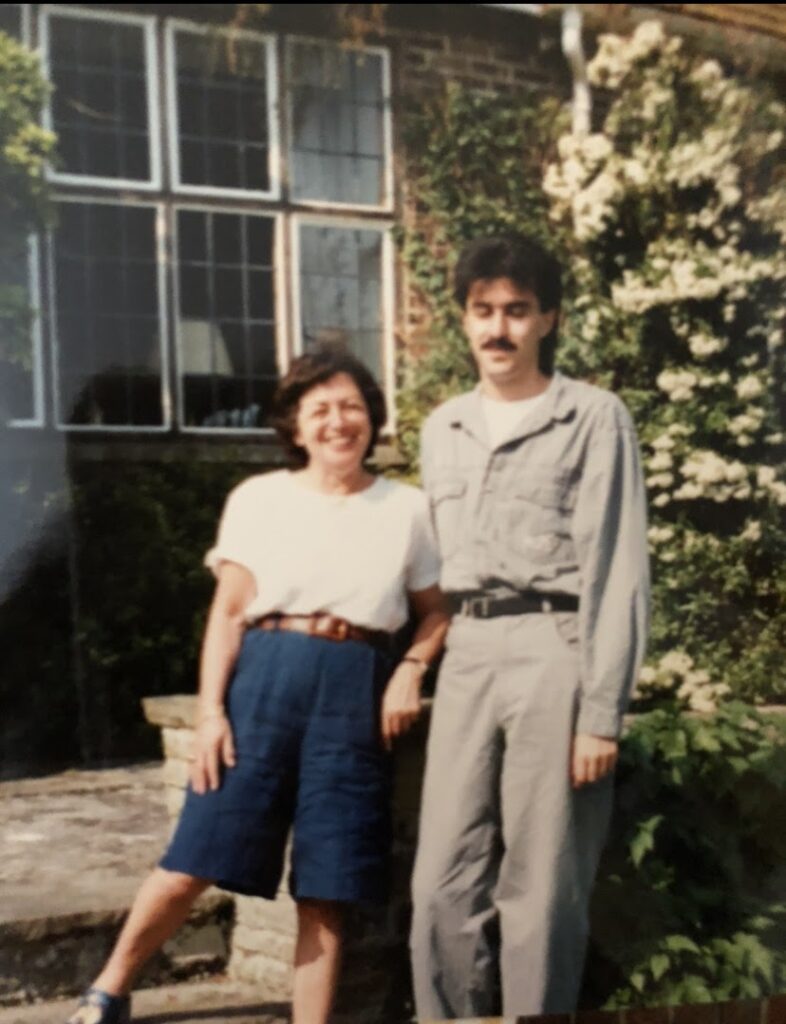

When Kookoo left my mother cried for days, she walked in circles until her stomach spun around and spewed green all over our floor. She would sit in our driveway, waiting for him to jump out, but he never came. What came instead was the body without skin, without wrinkled eyes and teeth—an empty body with a pile of fabric and words handed over in a ziplock bag. When I would remind my mum that they never found a body, she would remind me of what they did find, the wallet with the leather strap, the jumpsuit with blue lining and the words scribbled on paper that left us dizzied in pain until our bodies doubled like melting glass.

No one knows exactly what happened to Kookoo if his life ended in tragedy or a final performance to say ‘look at me.’ What we do know is a Kookoo in the ocean. A swollen Kookoo tumbling between layers of green.

Written by: Zanna Huth

Be First to Comment